Why classic change management models fail

Classic change models - simple answers to difficult questions

Change, transformation, transition - whatever title you want to give to the transformation of your organization, the concept of change cannot be grasped so clearly. Change is incredibly complex and affects organizations in all its dimensions: Strategy, structures, culture, processes, relationships, people, space and leadership. It is easy to lose sight of the big picture and lose control.

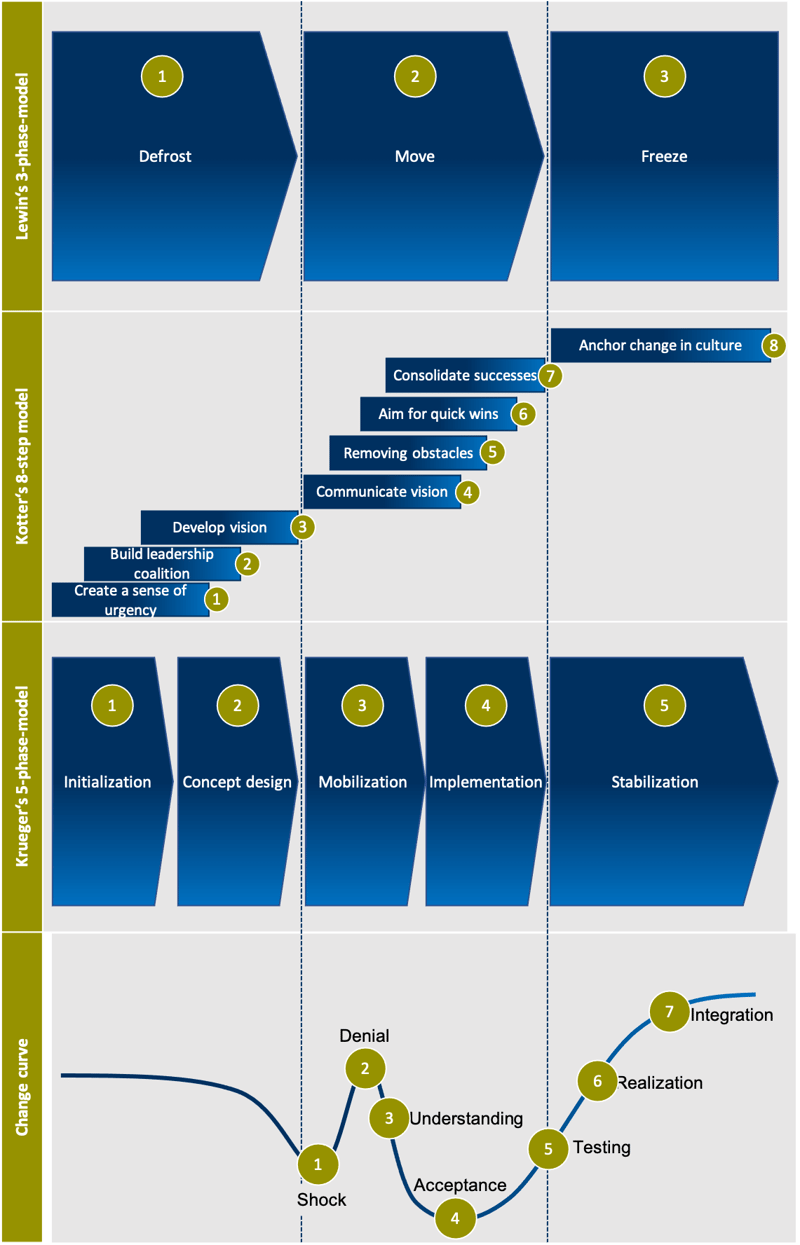

So it makes sense to look for a model that offers orientation in change processes. And indeed, a quick Google search shows: There are change management models that demystify change processes and offer structure and support. The first hits are usually Kotter's 8-step model, Lewin's 3-phase model, Krüger's 5-phase model or the change curve.

"Wonderful", you think to yourself and start managing your change according to one or more of these models. Because they all have one thing in common: they are easy to understand, simple in structure and structured in comprehensible steps.

What is striking about the structure and naming of most change models is the focus on a chronological sequence of steps, measures or organizational states. Let's take a closer look at the models.

Lewin's 3-phase model - change management from the frozen food counter

Kurt Lewin's 3-phase model has been around for a few years - but is often used in its original or slightly modified form in board meetings to summarize the upcoming transformation in a very simple way: 1. thaw 2. move 3. freeze. Quite simple. And quite logical.

Unfortunately, it is far too simplistic and one-dimensional. It is quite possible that during Lewin's lifetime in the first half of the 20th century, changes could be controlled in this way. But to "unfreeze" an organization of the 21st century and "freeze" it again? Unthinkable. And also impossible. Sure, even today there is sometimes more change and then less - but a mechanistic and self-centered understanding of organizations, as propagated by Lewin's model, will not help you manage your change.

Kotter's 8-step model - practical, but linear

So let's look at John Kotter's very widely used 8-phase model. In principle, he assumes a similar understanding of change as Lewin. Only he breaks down his model more granularly and takes a more practical approach, explaining per stage what needs to be done to shape the change.

This is more helpful than Lewin's approach. However, Kotter also views change as a step-by-step process, a recipe that managers can easily follow. What happens when things go backwards remains unclear.

And we can report from practical experience: The first 6 stages are comparatively easy to master (see graphic). Stages 7 and 8, on the other hand, can take months and years.

The model presents the most difficult, lengthy and complicated challenges, namely achieving and anchoring profound changes, simply as two final stages.

So you can put Kotter's model aside from stage 6 at the latest. Nevertheless, Kotter's model still strongly shapes modern change management. The use of a vision, the establishment of a change leadership team, and the formulation of a "sense of urgency" are three classic change recipes that are still used today, sometimes more, sometimes less successfully.

Kruger's 5-phase model - progress through regression

Moving on to Krüger's 5-phase model, which actually describes a typical management procedure. It reminds us of classics such as the PDCA cycle, but without the cycle, or the typical consultant approach "diagnosis, design, delivery" - Krüger adds stabilization.

Krüger's model reflects a similar understanding of change as Lewin and Kotter. In contrast to his predecessors, however, Krüger points out the possibility of regression, even if this is not apparent in the model itself.

For him, change is managed like a normal project in different phases. Complete phase, check off, next phase. The model is certainly helpful for change novices who want to get a basic orientation about classic change processes (if such still exist today). For advanced Reflect Notes readers like you, the model probably offers little new insight.

The Change Curve - Theoretically Good

Finally, let's take a look at the Change Curve. Unlike the previous models, it does not focus on managing the change process, but rather traces the course of emotions in a change. From shock to denial to insight, acceptance and to trying out new behaviors, and finally to realization and integration of new behaviors.

The change curve thus offers an insight into the emotional life and behavior of the people affected by or involved in the change. This is helpful in a way, as it helps change managers to anticipate employees' reactions and to intercept or mitigate them with the right methods (even if the model does not offer any clues on the right way to deal with emotional states).

However, like any model, the change curve is of course a simplification of actual change practice. In transformations, we see time and again that people react completely differently to change, that they move through the phases at completely different speeds, that some phases are skipped, and/or that some people never even reach a phase of insight.

In practice, we often see managers assume that the entire organization is moving smoothly through the curve. And we see managers overestimate their own progress on the curve. They think they are in the integration phase, but in fact they have only just gained the insight that the change affects them and have no idea that they are about to enter the notorious "valley of tears".

The big change management model comparison - all models at a glance

Our large change management model comparison superimposes the models listed above and shows: Whether 3, 5, 7 or 8 phases - all change models describe a period of stability and preparation, a period of change and a period of anchoring and stabilization.

How do linear models fit into a volatile world and a complex change environment?

The quick answer: Actually, not at all. As change practitioners, we can confirm that we have yet to accompany or observe a serious change process that followed a simple, linear pattern. And that's why we only resort to one of these models in our work when we are asked how change would work in a perfect, pardon the pun, one-dimensional world.

But companies and their cultures are not one-dimensional, and change has butterfly effects that cannot be squeezed into a linear model. And they are not completely "manageable" either. And they have spatial and temporal effects that go further and deeper than the most structured change manager is capable of planning and controlling.

So: take a quiet look at the models, write down your 3 most important insights in your notebook, and then put the models, the phases, the curves aside and focus on letting your company learn change. In a VUCA world and in digitalized and globalized organizations, change skills are more important than change planning. And patent recipes and "blueprints" have their best days behind them.

Conclusion

The most widely used change management models have not fared particularly well in this note. As change facilitators, we see little practical use in them. Kotter's model is the most likely to help us think of a few ingredients for a well-managed change process.

We believe: The considered change models are pure, highly abstracted theory and can provide orientation and security to change novices at the beginning of their training.

However, this security is deceptive. The seemingly simple steps and phases turn out to be a difficult web to untangle in practice. Therefore, we advocate using the classic change management models in a change introduction to show how easy it might have been in the past or how easy it could be if management COULD control all variables.

So we will try to show a more honest picture of change and a more practical, modern concept of change management in our notes and further publications and of course our consulting and advisory services.

Sources:

Kurt Lewin (1947) Frontiers in group dynamics. Concept, method and reality in social science. Social equilibria and social change. In: Human Relations. Vol. 1, No. 1

John P. Kotter (1995) Leading Change: Why Transformation Efforts Fail. In: Harvard Business Review. Vol. 2, Reprint 95204, pp. 59-67.

Wilfried Krüger (2014) Excellence in Change. Gabler Verlag, Wiesbaden